Always with the costs

It’s Federal Budget time, and next week is likely to kick off another batch of deeply unhelpful media coverage of how expensive and burdensome disabled people are.

The Budget will reveal some important numbers in this discussion, but they are unlikely to be treated as equally important. The first is the projected increased amount being spending on the NDIS, the second is the impact of the agreed 8% cap on that spending, and third is whether the promised reforms have any money allocated at all.

The first will be what is focused on, with descriptions of disabled people as unworthy and costly. I am so very tired of this discussion. Every single Federal Budget over the last decade has featured a version of this, with various folks out pontificating about how terrible it is to make sure disabled people have the support we need.

The cause of the cost increase is always seen as disabled peoples’ fault, for being disabled, for needing support, for wanting to have an equal life. The cause is never disability providers, rip-off merchants, exploiters and abusers. The cause is never those who lock up disabled people, take their support budgets and pocket those rising costs.

The cause is never the marketisation of social care, the commodification of disabled people and our support, the lack of anything that looks like regulation or oversight of disabled peoples’ money.

One of the themes of my writing over the last few years has been trying to unpick the connection between marketisation and disabled people having control over their support budgets. I’ve looked at how we got here, found documentation from the 1990s from disabled people arguing for their own funding for attendant care, for freedom from institutions and group homes. Nowhere in this work was a call for a ‘let the market rip’ approach, which is what we have now.

When the original Productivity Commission report into Disability Care and Support landed in 2011, it talked about how disabled people would act as consumers, buying the supports they wanted from this magical marketplace where they had all the power. This approach would deliver better services through competition, the Commission said, believing that:

“consumer control of budgets through self-directed funding, or even the option of controlling budgets, creates incentives for suppliers to satisfy the needs of consumers, given that they would otherwise lose their business.“

Thirteen years later, this kind of economic fantasy would be hilarious if it were not so bloody horrifying. Disabled people being kidnapped for their funding packages, ripped off, have little choice over services and supports, and providers offering pretty much the same old shitty models of support they always have.

The market system, with little to no oversight, has led to the costs of support rising so rapidly that both major political parties are wavering in their support for the NDIS, and moving quickly to remove disabled people from the Scheme. This is no accident, but the actual purpose of a market, so it shouldn’t be a surprise to any of the fancy economists that promote these approaches.

The lack of serious engagement by the political commentariat with this market failure means the only ‘solution’ they can find to rising NDIS costs are to punish disabled people and remove essential supports. There are no questions asked of the market model of public service delivery, or any serious discussion about whether this is how to deliver services at all from either the left or the right. Too often, I see left-wing critiques of the NDIS that do not understand why individual budgets are so important to disabled people, or right-wing critiques that fail to engage with exploitation and power.

So, instead of the same old bullshit Budget discussion, how about we have a discussion with an agreed shared set of facts, something that feels further away than ever.

It is true that the costs of the NDIS are rising, government don’t understand why, and it is totally freaking out the boffins in Treasury who hate social services spending, which in turn puts pressure on the economic decision makers in the Federal Government. Whether I agree with this or not, misses the point - this is a fact that has consequences.

In response to this, National Cabinet in 2023 decided to have a target of growth for the Scheme of 8% by 1 July 2026’, and here we are at the second key Budget discussion point. The current growth rate of the NDIS is projected to be at least 15%, and the date of that 8% cap/target is only two years away.

A cut of 7% to the NDIS is a lot - the latest Quarterly Report had the NDIS spending $20b between July and December 2023. This would shave $2.8b from the Scheme per year. These are huge cuts to the Scheme and we need to understand exactly what they mean, and who they will affect.

So why are costs rising, what are the various sets of facts put forward to explain this, and what are the real reasons?

The first reason always talked about for the costs going up is that there are more people getting support than expected, particularly kids. It is true that there are more children in the Scheme than the original designers imagined, but the costs of their plans aren’t very big, and those are not rising hugely. Additionally, the longer-term cost savings for our entire community by making sure kids get the support they need seems to be self-evident, as would be the costs to those children and their families of not getting support.

However, these kinds of benefits from investing in kids and families rarely get a mention in the NDIS context, while being strongly acknowledged in other conversations about how to support children.

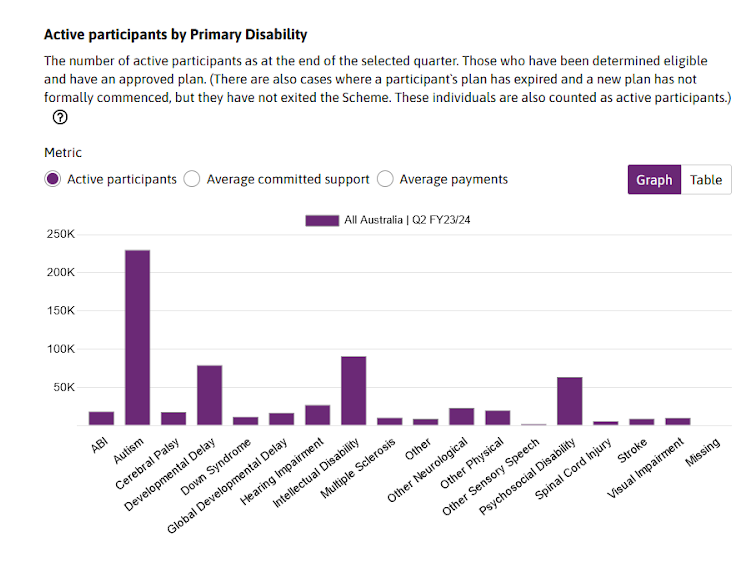

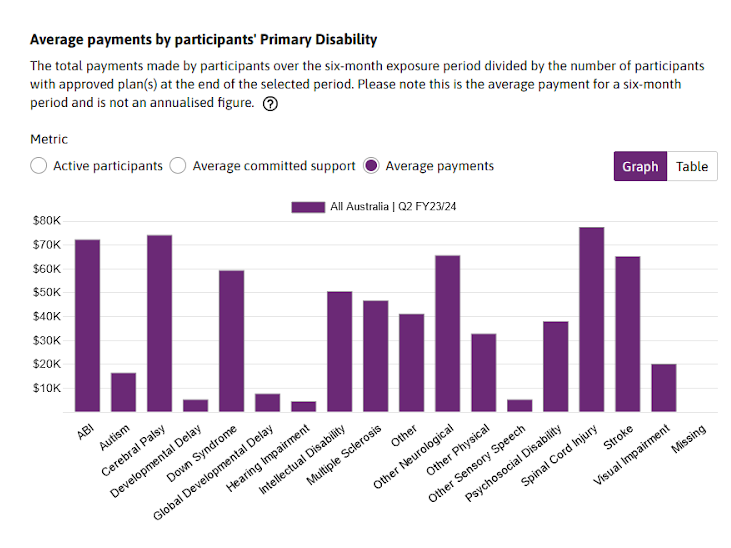

The second reason is the spectre of autism breaking the Scheme, the increase in diagnosis to get on the Scheme (hilariously wrong), and the weird obsession with autistic people from the Australian. There are lots of autistic folks in the Scheme, but again, their packages are often small, or they also have other disability, such as intellectual disability.

As you can see from the data below, the differences between the numbers of people with specific disability and the size of the average plans are large and important to understand. We don’t see the kind of freak outs about people with spinal cord injury or acquired brain injury as we do with autism or psychosocial disability. [And to be clear, I don’t want to see those kinds of reactions to anyone’s disability.]

The lifetime costs for autistic people who have missed out on support and systems are huge, including poverty and dying decades earlier than other people, but no one counts them or reports on them with same breathless abandon of our humanity.

The third reason for the rising costs that is rarely talked about is the huge increase in the costs of Supported Independent Living, or SIL. This is the intensive support that mostly people with an intellectual disability use, overwhelmingly in group homes or other institutional places.

SIL accounts for nearly a third of the total costs of the NDIS, and supports about 30,000 people out of the 650,000 on the Scheme. Inflation for SIL is now running at significantly higher rates compared to the rise in non-SIL costs.

Some of this increase is happening for very very good reasons that we need to be loudly supporting. When often older people with disability, who have lived all their lives in institutional places, get some choice about where they live and move into a more modern home, that is more expensive than the shitty 1950s group home they moved from. This. Is. A. Good. Thing.

But another reasons is the growth in unregistered and unregulated ‘SIL-homes’, where disabled people are plonked in a rented house in the suburbs and their plans drained with no accountability for actual support delivery. The Summer Foundation told the NDIS Review that:

‘SIL homes create a closed setting where the provider can restrict and control a participant’s access to other support services, as the provision of accommodation is conditional on their use of the supports provided.

Many of the disabled people who live in SIL homes need more funding, not less, to make sure they get a say over where and with who they live, and the types of support they want.

But instead, SIL is now the key funding source for most of the large providers, and increasingly for unregistered ones, keen to keep disabled people with the biggest plans.

And as the 730 Report showed last week, the private providers of some of these places are abusing disabled people every bloody day, with little or no consequences, except to get more of disabled peoples’ money.

The fourth reason, which the NDIS Review did talk about and name clearly, is the oasis/lifeboat issue – that NDIS supports are now the only supports available for disabled people, and that mainstream public services remain largely inaccessible and exclusionary for so many of us. Whether next week’s Budget delivers funding for these services and supports is a live question, as is what they are and when they will be delivered.

The fifth reason, which again, I’ve talked about at length before, is that the NDIS funds a very limited amount of what is deemed ‘disability-related’ support, which then leads to often the most expensive kind of support being funded, that delivered by a disability support worker, whether that is what disabled people want.

I could go on, but wanted to have something of a shared group of actual facts on the table as part of the Budget conversations, and also in the lead up to the new NDIS legislation being considered by Parliament.

The assumptions underpinning this proposed legislation rely on significant misunderstandings and willful misreading of why the NDIS costs are rising, and therefore, target areas that will do nothing of the sort, but will harm the most marginalised disabled people.

Nothing in the proposed legislation will have much impact on providers, either registered or not, nor on regulating the market, nor on delivering better quality services. Instead, parts will reinforce existing problems, and use the blunt instrument of removing disabled people from essential support to meet that 8% cap that looms large over all of this.